Betting Fast and Slow: System 1 and System 2

We all like to think we have reasons for doing the things that we do. Most of the time, though, we’re making decisions based only on the information that’s readily available to us. We don’t consider the things that we may not know. Instead, we simply do the best with the information that we have and forge on. By and large, our intuitions guide us through most situations in life unscathed. Therefore, it’s not in our nature to stop ask ourselves if we’ve missed anything. When it comes to sports betting, however, your intuitive judgement just won’t cut it, specially when it comes down to new gamblers. Think about your sports betting history and be honest. Has your approach been sound, or have you just let your intuition run wild with your bankroll?

In the book “Thinking Fast and Slow”, Daniel Kahneman explains that we aren’t all that rational. Especially when it comes to managing precarious situations that involve risk. Kahneman isn’t a sports bettor, but he is a Nobel Prize winning psychologist considered by many to be the founding father of behavioural economics. In the book, Kahneman summarizes several decades worth of research that he and the late Amos Tversky conducted. The studies explored how humans manage uncertainty and risk which immediately resonated with me as a sports bettor. The central thesis of the book is the dichotomy between the two modes of thought, System 1 and System 2, and it will totally change the way you think. Hopefully, it will also change the way that you bet.

System 1 (Associative Machinery)

System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with very little effort. It looks to form seemingly coherent links between cause and effect through pattern recognition and associative memory. It is intuitive, emotional and has no sense of voluntary control. This system constructs the best possible interpretation of a situation based on the often limited information that’s available. Associative Machinery (System 1) doesn’t allow for new information. It only represents ideas that have previously been activated and are easily retrieved from memory. Most of the development of this system takes place in early life.

System 2 (The Lazy Controller)

When we describe rational thought and rational decision making, we’re describing System 2 thinking. This system allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex calculations. This system is logical and sceptical and when activated, seeks out information to improve its ability to make decisions. The attentive System 2 is a controlled operation that has to be activated and requires a great deal of cognitive effort. Automatic responses that are now carried out by System 1 were shaped in System 2. Driving, ice skating, and playing an instrument are all good examples of skills that all become like second nature with deliberate practice and quality feedback.

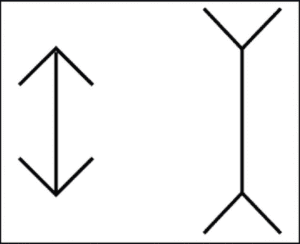

The Muller-Lyer Illusion

Kahneman describes System 1 as a machine for jumping to conclusions because regardless of whether or not the information it retrieves is relevant to the situation at hand, it measures its success on the coherence of the story it manages to create. Another problem with System 1 is that it doesn’t possess the ability to see gaps in logic. For example, the lines in the following image are equal in length. I bet you can’t convince your brain to see it that way, though.

This is called the Muller-Lyer Illusion and you can easily confirm the length of the lines with a ruler. Once you do that, you will have a new belief. If someone were to ask you about the lines, you would tell them what you know. You cannot, however, convince System 1 that the line with the outward facing fins isn’t the longer of the two. As Kahneman explains, in order to resist the illusion one must learn to mistrust their impression of the length of the lines when fins are attached to them.

A bat and a ball

When we think of ourselves, we think of System 2. The reasoning self that makes sound decisions based on logic, but System 2 is lazy. It really doesn’t want to do any hard work. System 2 will often delegate the hard work back to System 1, or worse, it will unquestionably accept System 1’s advice. For example, quickly consider the following question, but don’t try to solve it.

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 together.

The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

A very appealing and intuitive number came to your mind. The number, of course, is 10¢ and it’s wrong. Do the math. If the ball costs 10¢, then the total cost will be $1.20 (10¢ for the ball and $1.10 for the bat), not $1.10. The correct answer is 5¢ and no, it’s not a trick question. The first time I came across this question, 10¢ came to my mind immediately and I didn’t stop to check the math. I mean, you can answer questions like this in your sleep, right? Wrong. There are two facts that we know about the people that answered the bat-and-ball question incorrectly. They totally relied on their intuition, and they missed a social cue.

Thousands of university students have also been asked the bat-and-ball question and failure rates have been in excess of 80 percent. Even at prestigious institutions like Harvard, MIT, and Princeton, more than 50 percent answered incorrectly. In other words, don’t feel bad. Take it for what it is, a humbling learning experience.

Taking the next step

The world of sports betting is a cognitive minefield and understanding how System 1 and System 2 work will better equip you to navigate it. The next step is to develop an understanding of the heuristics and cognitive biases that are constantly in the background waiting to trip you up. Which brings me to – and leaves you with – the topic of my next article.

A heuristic is a mental shortcut used to solve a particular problem. It is a quick, informal, and intuitive algorithm your brain uses to generate an approximate answer to a reasoning question. For the most part, heuristics are helpful because they allow us to make sense of a complex environment, but there are times when they fail at making a correct assessment. When our heuristics fail to produce a correct judgement, it can sometimes result in a cognitive bias, which is the tendency to draw an incorrect conclusion in a certain circumstance based on cognitive factors.