Staring down Lou: How standing up for yourself can change a player’s career

Come to training camp, learn The Devils Way, and we’ll give you an appropriate contract. That’s what I was told by the New Jersey Devils organization in advance of the 2009-10 season.

Back then I was coming off my first year in the NHL: a 15-game cameo with the Tampa Bay Lightning. Was it all bunnies and rainbows? No. I only won four games in 13 starts. And my .887 save percentage was a good indicator that the American Hockey League was where I belonged at that stage of my career.

I was fine with that: I knew I had work to do. And it appeared that the Devils had an opening for me within the system. At the NHL level, Martin Brodeur was set to be backed up by Yann Danis, who had signed a one-year, one-way NHL contract during the offseason. And prospect Jeff Frazee had spent the previous year with the team’s AHL affiliate in Lowell, Massachusetts.

To me, there was clearly an opening at the AHL level. New Jersey didn’t have a fourth goaltender signed to an NHL contract, and I had a decent number of games under my belt at the top level. I’d even beaten Yann Danis the previous season when he was a member of the New York Islanders: a 1-0 shutout on home ice in Tampa Bay. It was my first win – and only shutout – in the NHL.

Everyone I spoke to – my agent included – thought New Jersey was bringing me in to play with Frazee in Lowell. It made too much sense. But I should have known it wasn’t that straightforward.

The Devils asked me to arrive in Newark early so that I could take part in development camp. Odd, considering I was 26 years old and had already attended five previously. I went to four with the Nashville Predators – the team that drafted me – from 2002 until 2005. And another with the St. Louis Blues in 2007.

Development camp is for prospects. Rosters are usually composed of players from junior hockey or just out of college. In other words: most of them can’t legally have a drink in the United States. Yet there I was, 26 years old, skating out for development camp after I’d just spent the final third of the 2008-09 season playing in the NHL.

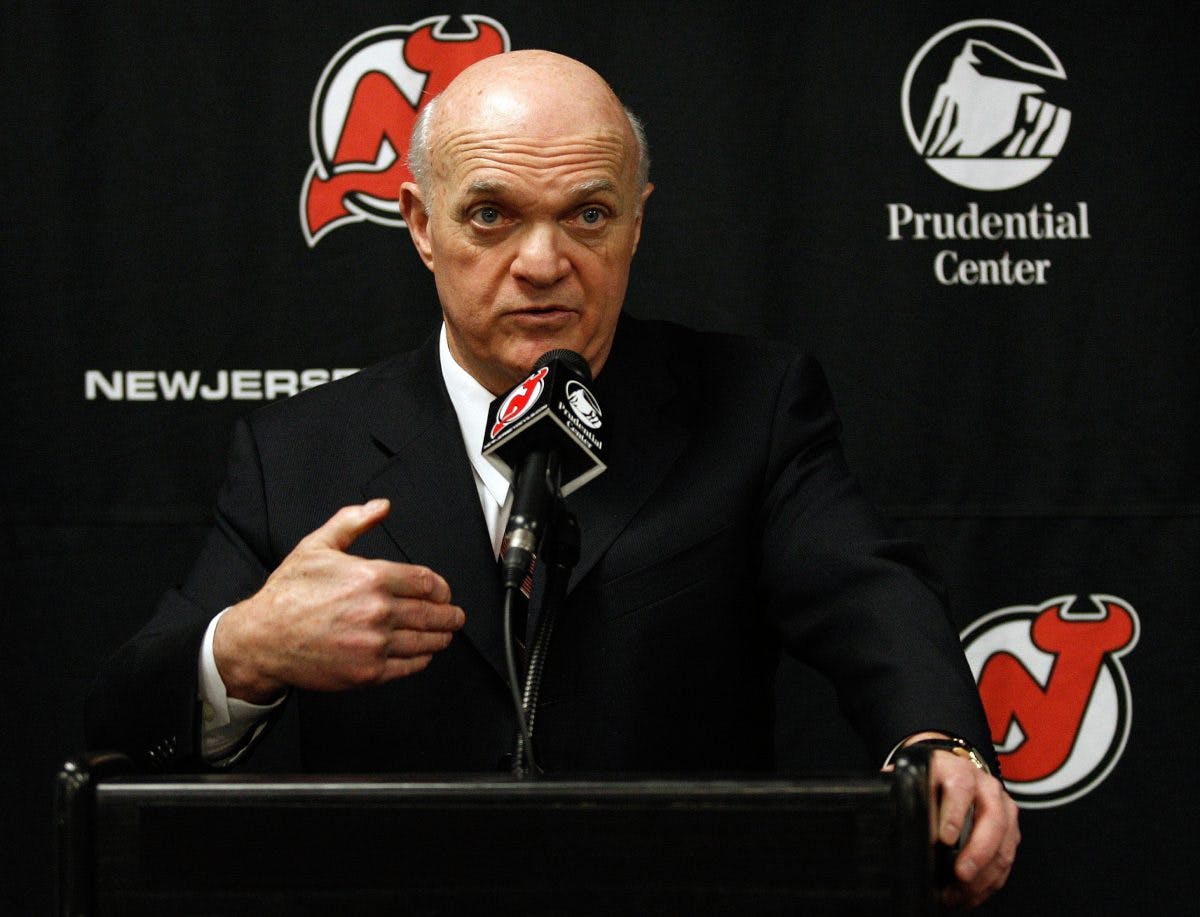

It was weird. But considering how quirky the Devils organization was under then-GM Lou Lamoriello, I took it in stride. They probably just wanted to get to know me better, I reasoned.

Nah. That wasn’t it. Within the first two days of training camp, I knew things were off. I was rostered with the rookies and placed in a locker room far away from the big club. I never met Brodeur – one of my goaltending idols – much less skated with him.

That was actually true of the entire Devils roster. I never met any of them. Despite playing in the NHL for a good chunk of the previous year, I only skated with rookies and minor-league players during the organized training camp sessions.

When my name was listed among the first cuts, I was pissed. And my training camp exit meeting with Lamoriello didn’t make me feel any better. He talked about how the organization wanted me in Trenton – the team’s ECHL affiliate – so I could learn The Devils Way.

I was irked that New Jersey didn’t have a plan for me at the AHL level. All that talk about an appropriate contract – which would have been either an NHL two-way or AHL one-way – seemed like bait designed to lure me into the system. New Jersey only wanted me as an insurance policy playing on a cheap, two-way AHL deal. And I saw through it.

Learning The Devils Way wasn’t a selling point to me. I was at a critical stage of my career. I needed a job in the AHL. And I felt like I’d been sold a bill of goods.

Here’s the thing: I wasn’t a Devils draft pick. I didn’t grow up in the system. By the age of 26, I’d already experienced life in six other NHL organizations. I’d spent time – whether during regular season play in the minors or training camp – with Nashville, Calgary, Chicago, St. Louis, Anaheim, and Tampa Bay.

I’d seen a lot in my young career. I’d learned the nuances between organizations and was well aware that Lamoriello ran the tightest ship in the NHL.

But to put it bluntly, I wasn’t terrified of Lamoriello like most of the Devils prospects. And with no contractual commitment to the organization at that time, I wanted my voice to be heard.

I looked at Lamoriello and said: “I finished last season in the NHL. I was told that I’d get a chance to come to camp and fight for a job. I don’t understand how I was supposed to show what I can do when I never skated with NHL players during camp.”

Lamoriello turned to the only other person in the room, David Conte. Who was New Jersey’s director of scouting at the time. And I’ll never forget his words.

“Is that true?” Lamoriello asked Conte.

Conte shuffled his papers, searching the rosters to find an answer.

“Yes,” Conte finally said to Lamoriello.

That was it. One word. Followed by an eerie silence that lasted far longer than it should have.

I was floored. Neither Lamoriello or Conte knew the answer. But the conversation was professional. I made my point without being argumentative. We all shook hands and I was off to Lowell the next day for AHL training camp.

I could see the writing on the wall: I was bound for the ECHL with the Devils. But since I was still a free agent, I started frantically contacting other AHL teams trying to find a job. Too little too late: most teams were already set in goal. Even the ECHL was filling fast with goaltenders. Soon I realized: I was stuck. My only real option was to accept a two-way AHL contract with the Devils.

Things were looking bleak for me until the final AHL preseason game in Lowell, when Frazee suffered a scary laceration on his neck. He ended up missing almost two months of game action, and in his absence, I played some of the best hockey of my life.

A 38-save shutout in my first appearance for Lowell. A 40-save shutout two games later. I was playing with a chip on my shoulder and plenty to prove. My career was on the line: I had everything to gain.

And you know what? The Devils rewarded me. When Frazee came back from injury, I stayed in Lowell. Instead of being sent to Trenton – where McKenna jerseys had already been made – I was told to get an apartment in Massachusetts.

My play warranted staying with the AHL club. I made it impossible for the Devils to send me down. But I also like to think my exchange with Lamoriello wasn’t forgotten. And respected.

In February of 2010, I signed a two-year NHL contract with New Jersey to remain with the organization through the 2010-11 season. In my eyes, the Devils made good on what they promised during the 2009 offseason. It just came a little late.

Looking back, I think what happened was a catalyst for my career. I had to fight tooth and nail for what I wanted, and frankly, deserved. But that’s the hard part of sports: what you deserve isn’t always what you get. Life isn’t fair.

It wasn’t the only occasion during my 14-year professional career that I had to reinvent myself. But it was the first time I ever put my foot down with management. Until that exchange with Lamoriello and Conte, I’d never stood up for myself.

I walked out of that exit meeting knowing all my chips were on the table. I felt empowered. Both sides knew where we stood. And from that point forward, everything was on my shoulders.

Proving your worth is an amazing feeling. But I think proving someone wrong is even more satisfying. While my time with the Devils started off rocky, and things went off the rails a year later during the 2010-11 season, I’ll always be thankful to Lamoriello. He could have easily buried me in the ECHL. Instead, he rewarded my play with a second chance to play in the NHL.

_____

Discover Betano.ca – a premium Sports Betting and Online Casino experience. Offering numerous unique and dynamic betting options along with diverse digital and live casino games, Betano is where The Game Starts Now. 19+. Please play responsibly.