To bridge or not to bridge: What to do with your RFAs coming off entry-level deals

In the salary-cap era, few things are more important than maximizing the money a team can save and the value they can get when they lock up their young talent after entry-level contracts. Not only are they trying to keep the player around for the long haul as a key piece of the franchise, the team also wants to make sure the contract is of the right value so that they can keep adding pieces to improve.

Usually this comes down to two choices: signing the player to a bridge contract to save money now and kick the can down the road or betting on them in the long run and locking them up long term. The former used to be the more popular choice, but as the game has changed and gotten younger, the latter has been relied on just as much, if not more.

There are many factors that come into a team deciding whether to go long-term or bridge their budding star, whether it be the current state of the team, how certain they are of the player’s skill, or whether they see opportunity to pay the player a bit more now at the expense of saving millions when they’re in their prime. There isn’t one universally correct path, so I’m going to look into what scenarios are suited for long-term contracts and and for bridge contracts.

Lock ’em up long term

Long-term extensions for young players are a much more recent tactic for teams. For a while it was only smart to hand out money to players who’d spent some time in the league and had proven to be worth that kind of term, and the rest of the young talent would be bridged for a few seasons to prove their worth. Even the young superstars of the early salary-cap years like Sidney Crosby, Evgeni Malkin and Steven Stamkos all only got five-year contracts off of their ELCs in an era where you could sign players for as long as you wanted.

But over the years, teams have started to realize that locking up their young talent is the more efficient way to go when managing the salary cap. Only 21 players who were 23 or younger and coming off their ELC were signed to 5+ year contracts in the first five years of the salary cap era. The next five years saw a bit of an increase in that number, but 2015 to 2019 nearly saw as many as the first 10 years combined.

| Time Span | # of Contracts |

| 2005-2009 | 21 |

| 2010-2014 | 34 |

| 2015-2019 | 51 |

(I decided not to do 2020 onwards because the pandemic slowed those types of deals down due to the financial losses the league experienced in that time, as well as the fact that there was a five-month stretch in 2020 where not a lot of contracts were signed.)

The biggest turning point was the 2011 offseason. A lot of the 2008 draft class was up for their first big pay day, and a lot of teams opted for long-term contracts. Stamkos, Luke Schenn, Tyler Myers, and Drew Doughty all signed to contracts between five and eight years, and one non-2008 draftee joined that trend in James van Riemsdyk with a six-year deal. Before those pacts, only 26 contracts with the previously mentioned qualifications had been signed in the salary cap era. Those five contracts marked the first of 80 to be signed over the next eight and a half years.

Why have more teams opted to go this route? While it has a chance of aging poorly (Schenn and Myers weren’t exactly high-end talents by the end of their deals after all), betting on your young talent before they’ve established themselves as elite talent means that you can get them at a cheaper price than you would after the fact, and it means that you’ll have them locked up to money well below their value once they hit their prime years.

On top of that, the more we’ve learned about aging curves, the more making those bets right out of a player’s ELC makes sense. I’ve previously alluded to all the examples from writers smarter than me like Eric Tulsky, Dom Luszczyszyn, and the Evolving Hockey twins about how a player’s prime is not in the 26-30 range like the popular belief is, but usually as low as 22 and high as 26. It’s not always universal, but there’s a reason that goal-scoring keeps going up as more and more young talent are being trusted earlier on in their careers.

So if a player is entering their prime right as they finish their ELC, wouldn’t it make sense to lock them up for the entirety of their prime, especially if it’s usually at a lower value than what they’re worth? You see plenty of instances where teams sign UFAs to overpriced long-term deals when they’re 27 to 30 years old, and it usually goes badly in the back half when they’ve aged out of the contract, so it makes a lot more sense to sign them for seven or eight years at 21-22 years old, and get them right until the end of their best years without facing any consequences in the later years of the deal.

There are two instances that make the most sense for locking up a player long-term. The first is if they’re a bona fide franchise player and you want to guarantee that they’ll stick around for a long time. The second is if the player hasn’t hit their stride quite yet, but you think it’s worth the gamble to pay a bit more money now to sign them long term and have them exceed their contract value in the prime of their careers.

The best example of the first contract is Connor McDavid. It was quite obvious that he was on the cusp of being the best player in the league when he signed his current eight-year contract, so he was given the highest AAV at the time to accommodate that. It’s allowed the Edmonton Oilers to work around him every year when building the team knowing he’s locked in and has the cap hit that he does, and it’s still managed to pay off in the back years because he’s still exceeding that value.

The second one is a bit more common because not every superstar establishes themselves in their first few seasons. However, the look of that deal has changed over the years. In 2016, Nathan MacKinnon got locked up to a $6.3 million AAV for seven years when he was only producing at a 50-60 point rate, but by year two of that deal, he catapulted to superstardom and that contract was a steal.

Today, one of the best examples is Jack Hughes. Hughes had just 52 points through two seasons in the NHL, but the New Jersey Devils bet on their first overall pick and gave him an eight-year deal with an $8 million AAV. Since then, he has 155 points in 127 games and that contract looks like a steal because he should be getting paid in the $11-12 million range.

It’s certainly a gamble, and it doesn’t always pay off, as deals that fit the bill like Christian Dvorak’s and Brady Skjei’s don’t exactly jump off the page as contracts you want to have, but they also aren’t hamstringing their teams either. And Colin White’s contract proved that if you pull the chute early enough on the deal, it can be bought out for a miniscule cap penalty as well.

Kick the can down the road with a bridge deal

So, after all that talk about the upside of long-term deals, they should just be given to every young player, right?

Not so fast. While it certainly has the most upside, it doesn’t always make the most sense.

Bridge contracts were always the popular choice in the earlier years of the salary cap because teams didn’t have the tools at the time to know whether it was the smart choice. It wasn’t until analytics came into the fold that teams had a better understanding of their players and predicting how they’d develop. Even now, it’s still not known for every player, and if the mystery has as much risk as it does upside, it makes more sense to delay the commitment for a few seasons when the player has established what they are.

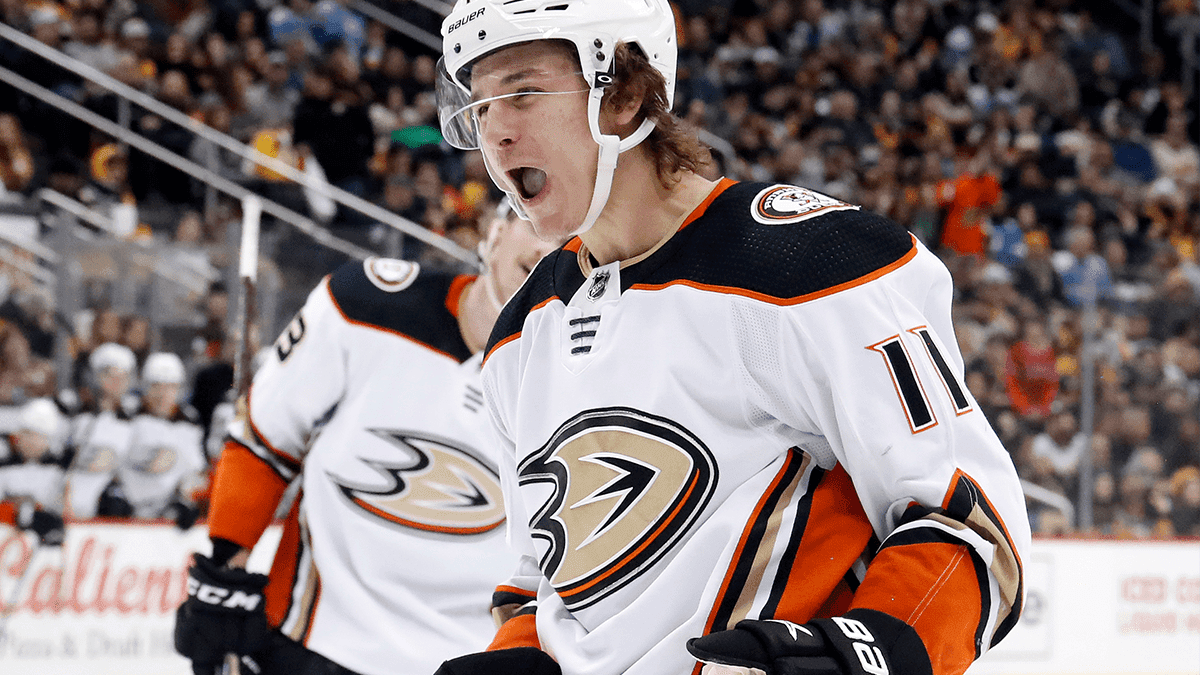

Take the recent signing of Trevor Zegras as an example. His flashy style of play has certainly given him attention and raised his stock in the league, so if you were going long-term, it’d likely be a deal similar to what the Devils gave Hughes, or what the Buffalo Sabres gave Zegras’ fellow 2019 draftee Dylan Cozens. But Zegras has also produced at only a 60-point rate each season, has struggled defensively and hasn’t necessarily proven to be a dominant playdriver. It’s not likely that a long-term deal for him really causes trouble for the Ducks, but it’s also a situation where giving him a few more years before deciding on him as a player, especially as he’ll now have more talent to work with, might not be the worst idea.

Another reason why a bridge deal is useful is if it’s the only option for the team at the time due to the constraints of the salary cap. If a team is right up against the cap but doesn’t want to move out too many pieces to make a contract with a young player work, it’s really the only option to get that AAV down to fit them under the cap.

The best example is the recent work of the Tampa Bay Lightning. It seemed like every offseason people thought that an RFA contract would finally be the one that caused cap problems for them only for the player to be bridged for a few seasons and then signed long-term the next time around. Nikita Kucherov, Andrei Vasilevskiy, Brayden Point, Mikhail Sergachev, Anthony Cirelli, all of them took a short-term deal at an insanely cheap price, and all of them have been paid handsomely since.

Is it the most optimal option in the long-run? No, as you can see by the Lightning’s depleting depth due to all the money tied up to those players now when they likely could have shaved off $1-2 million on each had they signed them long-term the first time. But I doubt Tampa Bay will complain about that considering it kept them ultra-competitive for almost 10 seasons and got them two Stanley Cups.

One more reason for signing bridge deals over long-term deals? Sometimes the young player just isn’t the kind of player you need to build around, and it makes more sense to sign them to shorter contracts. For every young player that deserves a long-term pay day, there are many who have established that their ceilings are those of a middle-six forward or second-pair defenseman – good, but not worth it to tie them up too long.

A good example for this type of player is Lee Stempniak. He was bridged to a three-year deal out of ELC after scoring 27 goals and 52 points in 2006-07, and was only signed to one- or two-year deals in his career after that contract. He had a solid career, often made for an effective middle-six winger and was never a detriment to his team. It wasn’t that teams didn’t want to commit to him because he was bad, just that it was never necessary to, and as a result he was perfectly rated, and sometimes underrated, throughout his career.

Signing a player to a contract when they aren’t fully established in the league is always going to be a gamble, so there is never a right or wrong answer between the bridge and long-term strategy. The more talented the player, the more it makes sense to make the bet, but it can still backfire if a team does it too haphazardly. And sure, bridge contracts make sense if teams always want to play it safe, but they have to pay their players eventually, otherwise teams may chase them away all together if there’s never any commitment.

The situation and the context for the team and the player is key in determining how to approach each young player and make the right move. It won’t be a home run with every player, but if a team is smart, they’ll win enough to benefit them as a whole and maintain a competitive window for years as a result.

_____

Discover Betano.ca – a premium Sports Betting and Online Casino experience. Offering numerous unique and dynamic betting options along with diverse digital and live casino games, Betano is where The Game Starts Now. 19+. Please play responsibly.