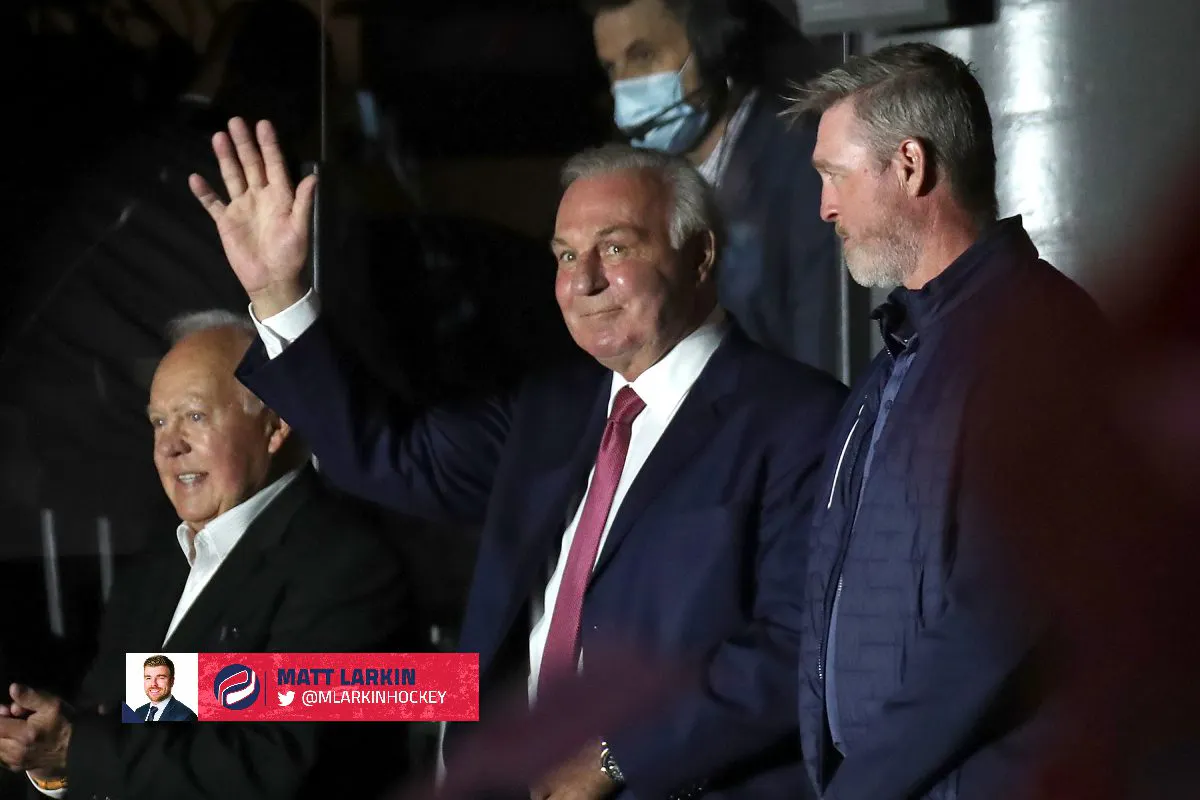

Remembering Montreal Canadiens icon Guy Lafleur: 1951-2022

There are superstars and there are folk heroes, athletes who ascend to mythic statuses. Tales get spun over the years about their greatness, the details gradually exaggerated until no one remembers what’s true and what isn’t.

Guy Lafleur, his hair flapping as he dashed down the ice, was one of those folk heroes. ‘The Flower’ had a sublimely effortless and pure hockey talent that captured people’s imagination. The most amazing thing about Lafleur?

The stories were usually true.

Take the incident that happened while Team Canada was training for the 1976 Canada Cup. Maybe you’ve heard someone spin the yarn before. Maybe you’ve read a version of it. But Hall of Famer left winger Steve Shutt, Lafleur’s longtime linemate during the Montreal Canadiens’ late-1970s dynasty, confirms it’s all true.

Coach Scotty Bowman had the team doing some dryland conditioning in Montreal and brought a specialized trainer to help. Early in the workout process, he took the team on a three-mile run. The goaltenders, as Shutt remembers it, decided to slack off and hang behind the pack after about 400 yards. But Lafleur felt the competitive juices flowing.

“We go for probably a mile or so, and Guy was right behind the trainer, and he just said, ‘Enough of this,’ and he just took off and started sprinting,” Shutt said. “And the trainer started sprinting after him, and they left everybody. But when the trainer finally caught up to Guy, Guy was back at the Forum, in the dressing room, sitting there having a cigarette.”

That was Lafleur. He couldn’t help but be more gifted than everyone around him.

As Shutt puts it, Lafleur would hang up his skates at the end of a season, not touch them until Day 1 of training camp the next season, and within two days he’d be operating at top speed.

He was magic on ice, playing with unbridled, improvisational joy. And that’s why his loss hurts the hockey world so much.

Lafleur passed away on Friday morning at 70 after a multi-year battle with lung cancer, his family confirmed on social media. In 2020, he underwent quadruple bypass surgery and, just a couple months later, had one-third of his right lung removed after doctors found cancerous tumors. He fought on for years after that. He’s survived by his wife, Lise, and their sons, Mark and Martin.

Lafleur was practically born to be a Montreal Canadien. Growing up in Thurso, Quebec and idolizing Jean Beliveau, Lafleur would sleep in his hockey equipment so he could save time the next morning, bounce out of bed and get to the rink for some extra ice time.

He carried that obsession with him into major junior hockey, where he posted legendary numbers, including 130 goals and 209 points in 62 games in 1970-71, his final season with the Quebec Remparts. In a meta moment, Lafleur, the obsessive hockey nut, became the source of a province’s obsession, the most feverishly anticipated prospect since Beliveau.

Canadiens GM Sam Pollock had to have Lafleur – or the similarly hyped Marcel Dionne – so badly that the planning process began a year before they were draft eligible in 1971. Pollock traded Montreal’s first-round pick in 1970 to the expansion California Golden Seals in a move that included the Habs getting the Seals’ 1971 first-rounder, anticipating that they’d be bad enough in 1971 to yield a No. 1 overall pick to Montreal. The plan worked in the end, and the Habs took Lafleur.

The pressure, however, was smothering. Lafleur wore No. 4 in junior but declined to take it from the retiring Beliveau, lest it invite even more hype. Lafleur wasn’t an instant star when he broke into the NHL. The pressure played a role, yes, but Lafleur was also at a disadvantage compared to other young Francophone stars breaking into the NHL at the time, explains nine-time Stanley Cup winning coach Scotty Bowman, who shepherded Lafleur through the Habs’ dynasty. Players like Dionne, Gilbert Perreault and Rick Martin joined weak teams who offered ice time for days, whereas Lafleur, Bowman said, joined a team full of future Hall of Famers coming off a 1971 Stanley Cup victory.

“He was such a skillful guy – his judgment of skating, passing, shooting, he was top of the line,” Bowman said. “It was just a matter of getting acclimatized to a team game. The ice time was not the same as you have in junior. He was always a good skater. He was a freewheeling skater. Good edges. You could see that he was a special player, but it was going to take time.”

The Habs already had the likes of Pete Mahovlich and Henri Richard up the middle. That’s why Bowman moved Lafleur to the right wing, where his career blossomed. He spent time with Mahovlich and, later, Jacques Lemaire at center, but Shutt was the constant running mate on the left side. He and Lafleur spent copious hours together off the ice. It was imperative to do so, Shutt recalls, because they were trying to form a bond that would feel automatic on the ice. To keep up with Lafleur, blessed with blinding speed and a booming shot, you had to think incredibly fast.

“One day, we were sitting around, and he says, ‘You know, when I’ve got the puck, I don’t like to have a plan. I just like to go,’ ” Shutt said. “And I said, ‘Well, I’m playing with you. What am I supposed to do?’ And he looked at me and half smiled and said, ‘That’s your problem.’

“The one thing you did know when you played with him was that you had better be at the top of your game, because otherwise he’s going to leave you in the dust. He certainly made me a better player. I had to be up for every game. And it didn’t matter who we were playing against.”

The talent and opportunity finally merged by Lafleur’s fourth NHL season, in which he began a run of six consecutive campaigns with at least 50 goals and 100 points, a streak bested only by Wayne Gretzky. Lafleur earned six first-team all-star nods during that stretch, as well as three scoring titles, two Hart Trophies and three Lester B. Pearson Awards for the most outstanding player as voted by the players. He won his first Stanley Cup as a 21-year-old in 1973 but was the feature attraction on the powerhouse Canadiens that won four straight titles between 1976 and 1979. He was equal parts goal scorer and playmaker. His athleticism and creativity with the puck helped him overcome the constant shadowing or double teams opponents deployed against him.

The back half of Lafleur’s career was more of a rollercoaster. In the post-dynastic years, his pure offensive style didn’t always jive with a Habs team transitioning to a more defensive system. He was involved in a serious car accident in 1981. But even as his incredible career peak began to fade in the rearview mirror, he never stopped loving the sport. He retired in 1985 but returned to the NHL by 1988 to play three more seasons in his late 30s, one with the New York Rangers and two with the Quebec Nordiques. He was just the second player after Gordie Howe to play NHL games after being inducted to the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Lafleur was never the loudest presence in the dressing room, though he did some occasional sponsorship deals and appeared in various ads after his playing career. He ran a helicopter rental company after his retirement, owned a restaurant and was named to the Order of Hockey in Canada in March 2022. But he didn’t crave spotlight – just like he didn’t during his playing career.

Why? Because the sport itself was his true love. It’s what mattered. It was why he had his equipment on up to four hours before a game started. And it endeared him to his teammates.

“That’s why they loved him: what you see is what you get,” said Shutt, who kept in touch with Lafleur in their post-retirement years. “He was honest and open. He really didn’t have any airs about him. He didn’t think he was better than anybody else. He thought he was part of our team. And, really, that was the strength of the Montreal Canadiens in that era.”

“He was not an outgoing guy, more on the shy side, but he didn’t try to do anything else except play hockey,” Bowman said. “That was his life. Hockey was his life, and that’s why he took a bit of time, because he had a high expectations to be what he eventually was: which, to me, he was the No. 1 forward of the 70s.”